Bölkow Bo-46 – Credit Wikipedia

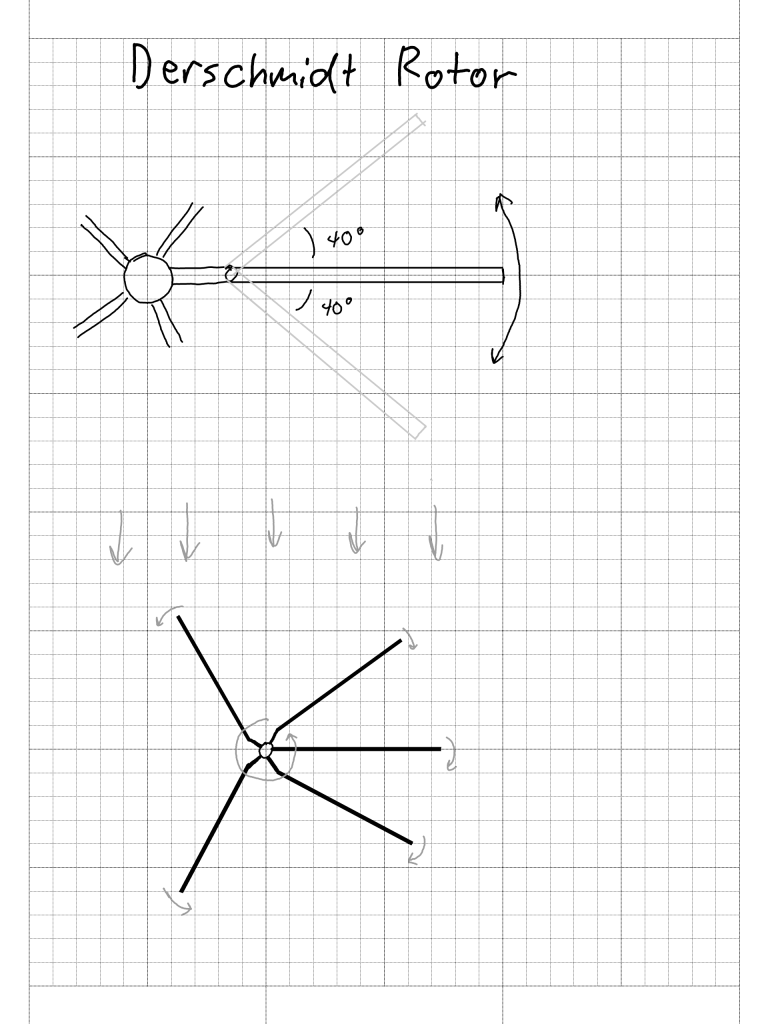

Explaining the Derschmidt Rotor

The Origin Story

Helicopter rotors have to have relatively thin blades to reduce drag that still carry very large bending loads to transmit the lift to the rotor hub. Because of the asymmetric loads on the rotor disk that’s spinning at high RPM you also have to deal with extremely powerful gyroscopic effects. The easiest and lightest solution was and is to embrace the gyroscopic effects and let the blades move around a little. When the Derschmidt rotor was invented in the early 1960s, helicopter rotors used aluminum blades that that couldn’t bend very far, so rotor heads had to have a complex series of bearings for each blade so that they could move around the little bit that they needed.

Derschmidt’s idea was that instead of a complicated set of multiple bearings, he would use one large bearing with a much larger range of motion that changes the rotor dynamics so that it doesn’t need the other bearings. This simplified the rotor compared to existing aluminum bladed systems, dramatically increased the theoretical top speed, and made it more efficient at high speeds.

How it Works

In a derschmidt rotor system, each of the blades can “waggle” about 40 degrees ahead or behind it’s position on the rotor head. When the rotor is moving forwards the extra drag on the advancing side causes it to waggle backwards, and then waggle back forwards on the retreating side. This decreases the effective speed of the advancing blade and increases the effective speed of the retreating blade, each by up to half the average tip speed, significantly reducing the asymmetry. By designing the resonant frequency of the waggle to be the same as the rotor RPM, the smaller remaining drag asymmetry can still drive the blade back and forth through a large angle. Because drag scales with velocity squared, reducing the speed asymmetry between the advancing and retreating blades dramatically reduces the total power required to drive the rotor in forward flight.

Increasing the retreating tip speed and reducing the advancing tip speed also allows for a much higher theoretical top speed. Typical helicopter rotors have an average tip speed of around 300 kts. At around 500 kts total airspeed, drag starts to rise sharply due to compressibility effects, and at a total airspeed of under 100 kts, the retreating blade just can’t produce enough lift. That means that the conventional single rotor helicopter has a hard limit of about 200 kts of forward speed, because at that point the advancing blade has a total speed of 300 + 200 = 500 kts, and the retreating blade has a total speed of 300 – 200 = 100 kts. For a derschmidt rotor that adds 150 kts to the retreating blade and subtracts 150 kts from the advancing blade, you don’t hit that limit until 350 kts of forward speed. It can push a little past it to the 380 kt top speed derived from the original wind tunnel tests even without stub wings because at that speed you can start reducing the load on the rotors meaningfully with just body lift. It’s efficient cruise speed is around 260 kts

Why it Was Abandoned

The much more complicated dynamics of the derschmidt Rotor, not surprisingly, lead to it being very difficult to control. The control problem was not that hard to solve, but because it had to be solved mechanically, the rotor head lost it’s original simplicity compared to conventional aluminum bladed rotors. While it still had higher performance, it was still new and no longer any cheaper.

The other major problem for the derschmidt rotor was the invention of composite rotor blades that were much stronger and could flex enough without breaking to eliminate almost all of the complex bearings in a conventional rotor. This dramatically reduced the cost and complexity of conventional rotors, but because of the much larger range of motion, couldn’t do the same for derschmidt rotors.

Derschmidt rotors were originally conceived as a way to get higher performance from a simpler system, but then the derschmidt rotor got more complex, conventional rotors got simpler, and no one at the time cared enough about higher speeds, so the project was abandoned.

Why It’s Worth Another Look

More powerful engines and advances in helicopter design have pushed up against the 200 kt speed limit, and the way helicopters are used has evolved and grown. Unlike in the 60s, there’s now real demand for higher speed and longer range rotorcraft for all sorts of applications like search and rescue, medivac, disaster logistics, and military operations.

The control problems that the original derschmidt rotor had to solve mechanically in the early 60s can now be solved digitally with modern fly by wire. The system would still be more complex than a conventional composite rotor, but not by nearly as much.

Why Use a Derschmidt Rotor

High Speed Vertical Lift

In search and rescue and medivac, high speed long range vertical lift saves lives. The faster you can cover ground and the more ground you can cover to search a large area or get to the people you need to rescue the better your chances are of getting to them before it’s too late. The faster and farther you can fly directly from picking someone up to the medical they need the more likely they are to survive.

In a military or disaster relief context, it lets you move people and supplies farther and faster to places with no functional infrastructure. That means getting more people things where you need them faster to get the job done. It also lets you move those vertical lift assets longer distances to where their needed without relying on arial refueling or strategic air lift.

In a naval context, it lets you counter pirates, enforce laws, and render aid farther form friendly shores or farther from the launching ship.

High speed long range vertical lift isn’t needed for everything, but it’s incredibly valuable and saves lives when you need it most, and it’s only going to become more valuable as we find new ways to use it.

Comparison to Tiltrotors

The well known solution to high speed long range vertical lift is the tiltrotor, made famous by the V-22 Osprey. They can match the speed and efficiency of some turboprops in cruise flight while still being able to hover effectively.

The new V-280 Valor / MV-75 second generation tiltrotor is really impressive. With it’s lightweight composite wings and low disk loading, the hover efficiency gain of not having a tail rotor fully compensates for the extra weight of the wings. The relatively high aspect ratio wings also give it incredible cruise range and efficiency. For a Blackhawk size system, a tiltrotor really can’t be beat in most applications.

They do have some limitations though. The weight penalty of the wings scales with the cube of wingspan, and the rotating gearboxes and cross rotor driveshafts don’t scale up to extreme torques as well, so the V-22 is probably about the maximum practical size for a tiltrotor. No, quad tilt rotors aren’t safe because there isn’t a good way to interconnect all 4 rotors so that you don’t flip if you loose an engine. Tiltrotors also take up a longer storage space than conventional helicopters even when folded, and don’t really work for things like airborne early warning or wing or side mounted weapons where the prop rotors can really get in the way.

The Failure of the Sikorsky Advancing Blade Concept

The Advancing blade concept was developed by Sikorsky as a way to break the 200 kt helicopter speed limit with something more agile and more efficient in hover than the V-22. They built prototypes for a light helicopter called the S-97 Raider and their future vertical lift proposal with Boing called the SB-1 Defiant.

The way it works is that they use a coaxial rotor with a pusher propeller and slow the rotors down at high speed to avoid compressibility issues on the advancing blade. This causes the retreating blades to stall, and with normal flexible rotors, gyroscopic procession would make both rotors push the nose up. To make everything balance, the rotor head and blades have to be made rigid enough to completely resist gyroscopic procession and all of the normal flapping of helicopter rotors. Getting that rigidity on thin rotor blades is much harder and heavier than on a tiltrotor’s much thicker and slightly shorter wings, making the advancing blade concept scale up poorly, even just to Blackhawk size.

The system also has a lot of drag because the retreating blades on the slowed rotor have air flowing over them backwards when flying at high speed. Combined with their extra weight, that makes them just not that much faster or more efficient than conventional helicopters. As coaxial helicopters, they also don’t have very good yaw authority while hovering.

The Best Places for Derschmidt Rotors

The biggest advantage of the derschmidt rotor is that they scale up just as well as a conventional helicopter, so unlike a tiltrotor, you can build one with the payload capacity of a heavy lift helicopter like the CH-47 or CH-53. That lets you build basically a VTOL C-130 that can also sling load oversize cargo over much longer distances than a conventional heavy lift helicopter.

Derschmidt rotors also shine, at least in a military context, when you need more speed, efficiency, or cruising altitude than you can get out of a conventional helicopter, and a tiltrotor either doesn’t fit or the prop-rotors get in the way. Some good examples would be VTOL airborne early warning, an attack helicopter than can escort the tiltrotors, or a naval helicopter where even a folded tiltrotor just doesn’t fit.

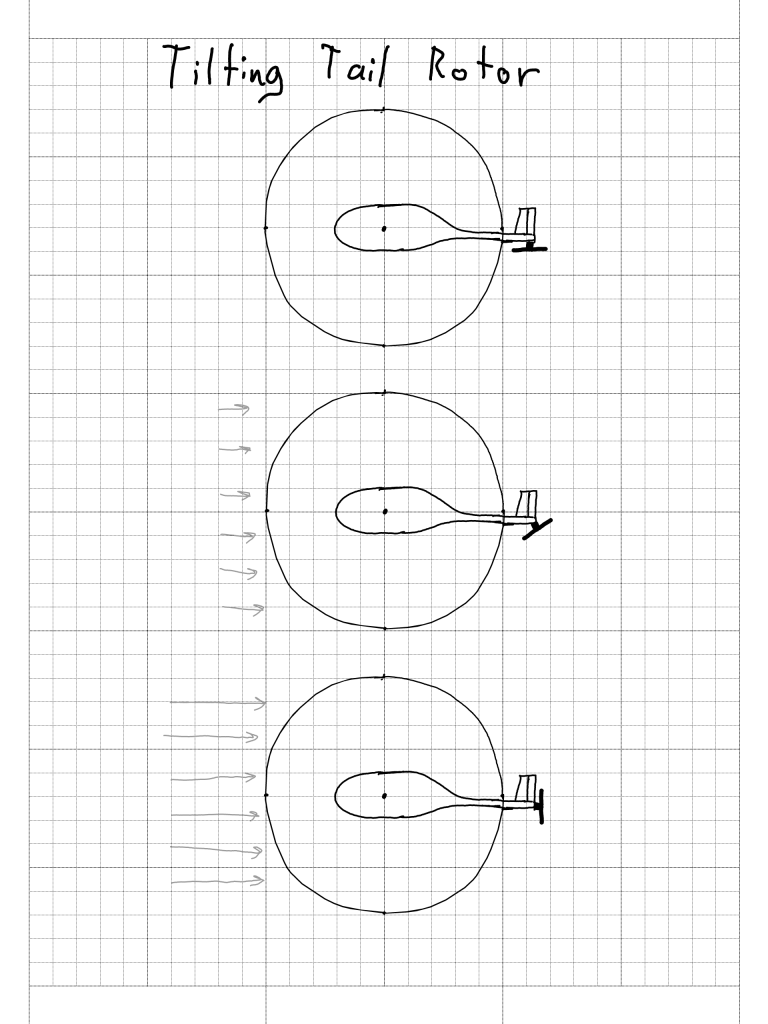

Adding a Tilting Tail Rotor

A helicopter’s tail rotor is used to counter the torque of the main rotor so that the helicopter doesn’t spin out of control and provides yaw authority. Modern helicopters also have large vertical tails that can do the same job more efficiently as you get enough forward speed. Once you reach around 70 kts, the vertical tail is doing all the counter torque, which saves the 10% fuel burn, but the tail rotor is now pure drag.

Using the main rotor for forward thrust also starts to become less efficient as you speed up. This is partly because it increases the load on the main rotor in a flight regime where the retreating blade has very high induced drag. It’s also partly because higher forward thrust from the main rotor requires the helicopter to tilt farther forward, which eventually starts tilting the body downwards, dramatically increasing body drag and pulling downwards. All that make a pusher propeller much more efficient for forward thrust at high speed.

Solutions that have been proposed in the past include shrouded tail rotors or rotor-less counter torque systems that are low drag in forward flight combined with a pusher propeller, or a vector able ducted fan. Those work but they’re heavy and don’t scale up to really large helicopters. As a better alternative that scales better, I would propose a tilting tail rotor.

By using the gearboxes developed for the MV-75 tiltrotor with it’s prop-rotors that tilt independently of the nacelles, you can build a tilting tail rotor that easily scales up to the largest helicopters in the world. While hovering, it faces sideways like a conventional tail rotor to provide counter torque. At high speed it tilts backwards to it’s cruise position, providing efficient forward thrust and eliminating the drag of a conventional tail rotor. Because of the power margin available in hover for yaw authority and gust loading, and the trigonometry of thrust vectoring, you can even start titling the tail rotor back slightly while hovering for level body acceleration.

Some Examples of What’s Possible

Long Range Heavy Vertical Lift

With a derschmidt rotor and tilting tail rotor, you could build a CH-53K with probably 4x the range. That could match the range and payload of older model C-130s while being able to take off and land vertically, with a cruise speed of ~260 kts to the C-130s 290 kts.

In naval operations, it would easily outperform the C-10 Greyhound or CMV-22 carrier delivery aircraft in range and payload and could land on any ship with a big enough flight deck. It would actually out mass what’s possible to launch from a catapult at all, and is fast enough to refuel jets, making it the heaviest tanker you could put on a carrier.

Compact High Speed Helicopter

You could build a compact helicopter with 80% the range and cruise speed of an MV-75 tiltrotor that fits in the hangers of existing naval ships designed for smaller Blackhawks. That would dramatically extend the range at which they could do everything from rendering aid or fending off pirates to hunting submarines.

Effective Helicopter Airborne Early Warning

The derschmidt rotor and tilting tail rotor configuration also opens the door to truly effective VTOL AEW. Conventional helicopters can’t fly efficiently at high enough altitudes, giving up over 50 nmi of radar horizon relative to an E-2 Hawkeye, and a tiltrotor’s proprotors in cruise configuration get in the way of an practical radar installation.

The derschmidt rotor allows it to use a 30% higher rotor RPM for higher lift and retain nearly symmetric tip speeds on the advancing and retreating blades at 200 kts forward airspeed. At the cost of an only 300 kt top speed, that gives it an incredible lift capacity for long endurance 200 kt cruise at the same altitude as the E-2 Hawkeye with powerful conformal radars.

Leave a comment