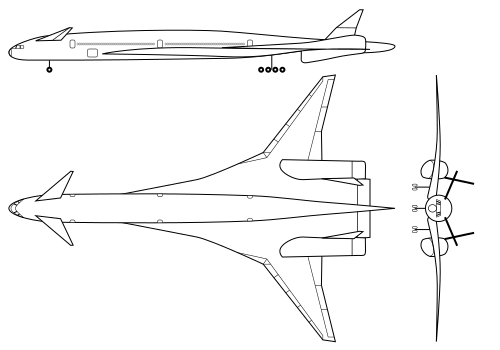

Artists Rendition of the Boeing Sonic Cruiser

Fleet Size: Why the Concorde Failed

Minimum Viable Fleet

Aircraft need crew training and spare parts, which require facilities and production lines. There’s a minimum size training facility you can build and spare parts require at least one set of tooling. If you don’t have enough aircraft in the fleet to keep that infrastructure in continuous use training crew and building spare parts, you still have to maintain it when you aren’t using it and can’t benefit from economies of scale. That starts to make every spare part and the training for every crew member extremely expensive.

The general rule of thumb I’ve heard for commercial aircraft is that you need about 300 planes of a given type to have a sustainable spare parts and maintained pipeline. There were only 24 Concordes built. That not only made crew and spare parts expensive, but is what ultimately forced their retirement. They just ran out of spare parts and it was too expensive to order a new batch.

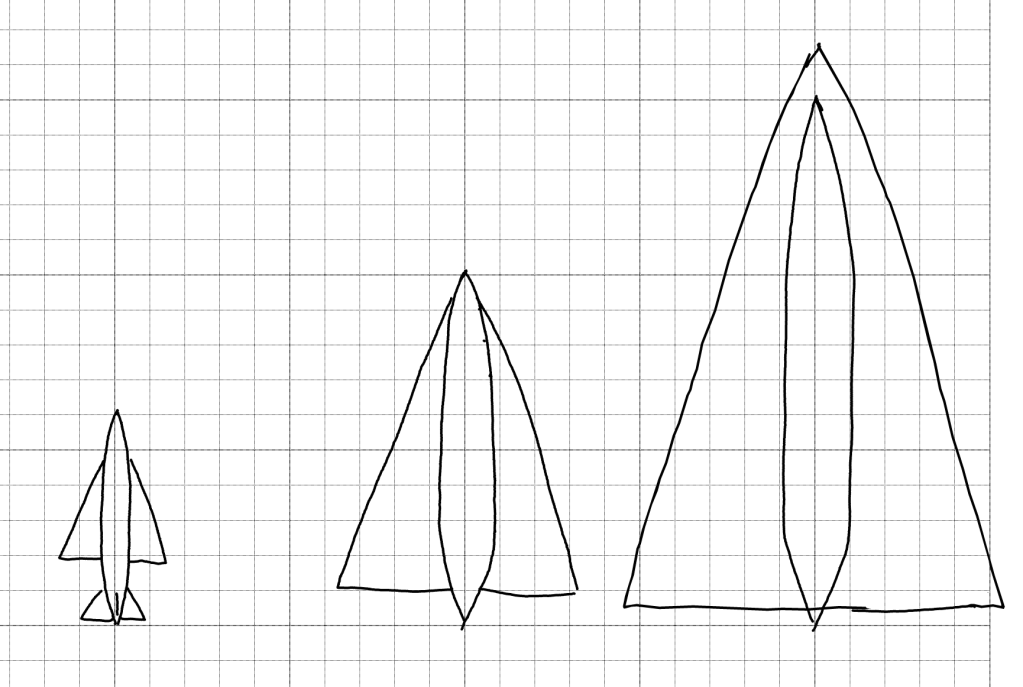

What Made the Fleet So Small

Part of why the concord had such a small fleet is that there were just very few routes it could fly. It only had a range of 4500 mi, and had relatively poor efficiency when flying subsonic, so it couldn’t quite cross the pacific even with a stop in Hawai’i, or go to cities too far inland. Especially with it being too expensive for most leisure travelers, that really limits how many city pairs could support daily service.

One of the other limits imposed by the concord’s short range is that the subsonic flights it was competing with were not that long. That means that the alternative to the “economy class” sized seats on the concord was a lie flat business class seat on a subsonic airliner where you can comfortably sleep through the whole flight and wake up ready for work when you get there for less than a concord ticket.

When the concord was built, that limited regular service to New York and DC to London and Parris, with less frequent service to a few other destinations. In a more recent context, you could probably add flights up and down the east Asian coast from Beijing to Singapore, and the major cities in between, but I suspect you would still struggle to support more than 100 aircraft.

The Need for an 8000 Mile Range

An 8000 mile range opens up the long nonstop east west routes across the pacific and north south routes up and down the Atlantic. That opens up an order of magnitude more viable city pairs, like New York or London to Rio or Buenos Aires and the US west coast to Asia.

Those routes that require a globe spanning range are also ones that take 10+ hours on a subsonic airliner, at which point speed becomes much more valuable because 10 ish hours is the longest flight where most people can sleep through everything except meal service. A lot more business travelers (and people in general) are going to be willing to pay extra to cut down a 14 hour fight than a 6 hour one.

A supersonic airliner needs an 8000 mile range to be economically viable because that’s the only way to capture enough demand for it’s higher priced tickets to build a sustainable fleet size.

Technical Challenges

Delta Wing Size Limits

As an airliner, it has to have safe takeoff and landing speeds, which puts a minimum size on the wings. Because wing area increases with the square of length and mass increases with the cube of length, the wings have to get bigger relative to the plane as the plane gets bigger. For a subsonic airline, this is largely not an issue, but for a supersonic airliner that can limit how big of a plane physics lets you build build, which matters because bigger planes are more fuel efficient and have longer range.

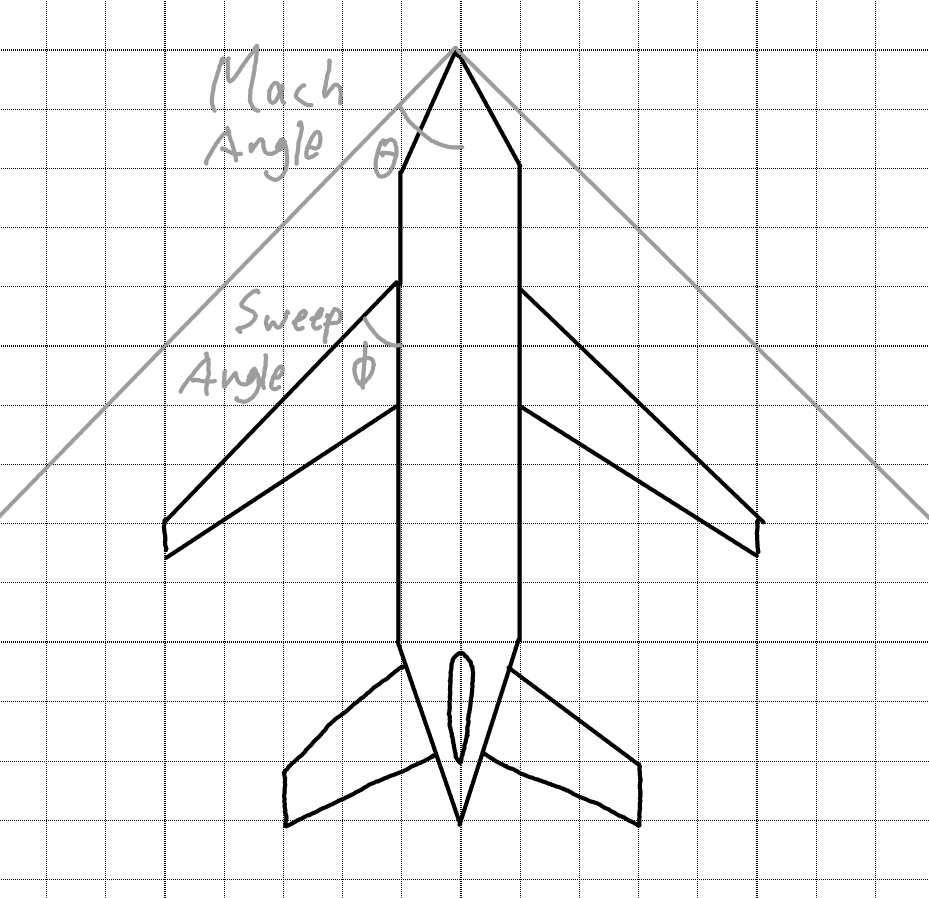

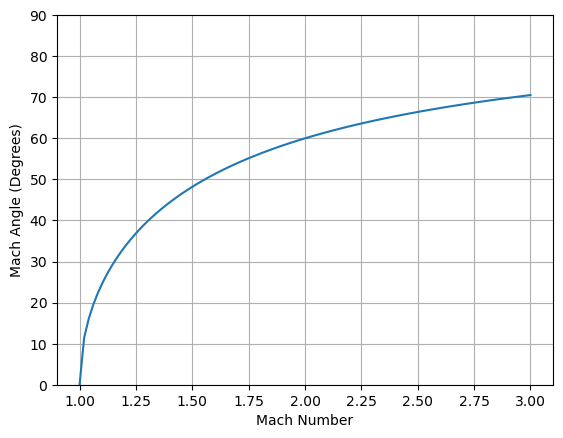

When something goes faster than the speed of sound, it creates a shock wave. The angle of that shockwave depends on the Mach number. That angle is basically just trigonometry saying, at what angle is the component of airspeed perpendicular to the surface equal to Mach 1. If you have something like a wing that’s swept back less than the Mach angle, you get a big draggy bow shock in front of the leading edge.

That means that to fly efficiently at a given Mach number, there’s a minimum wing sweep angle equal to the Mach angle. Wings that have a higher sweep angle tend to produce less lift per area at a given speed. The maximum wing area, a delta wing with the minimum sweep angle that’s the length of the plane, also gets smaller as the minimum sweep increases. Since you need enough lift at a safe takeoff and landing speed, that effectively puts a maximum size on the plane that gets smaller as it’s cruise speed increases.

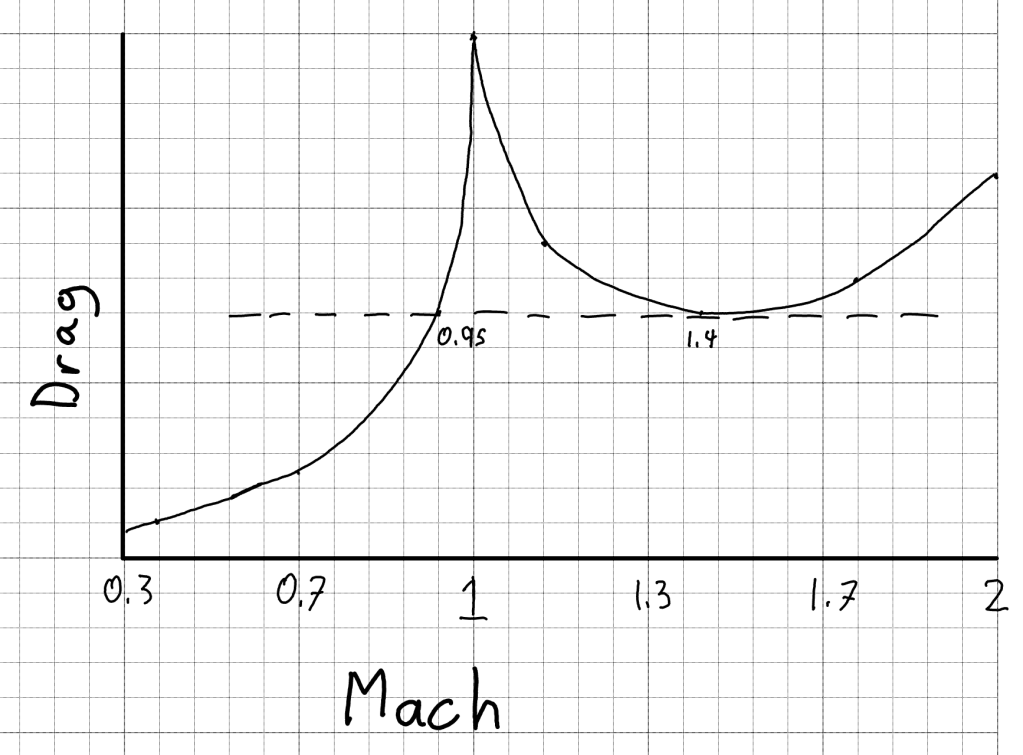

Modern widebody airliners typically have a wing sweep of about 45 degrees to maximize their efficiency. With good design that wing sweep works up to about Mach 1.4. Combined with some things like area ruling and wave drag, a well designed plane can get about the same fuel per mile at Mach 0.95 and Mach 1.4. Somewhere between Mach 1.5 and Mach 1.6 is probably the maximum for a 787 or A350 size plane with fixed wings.

Engine Efficiency and Noise

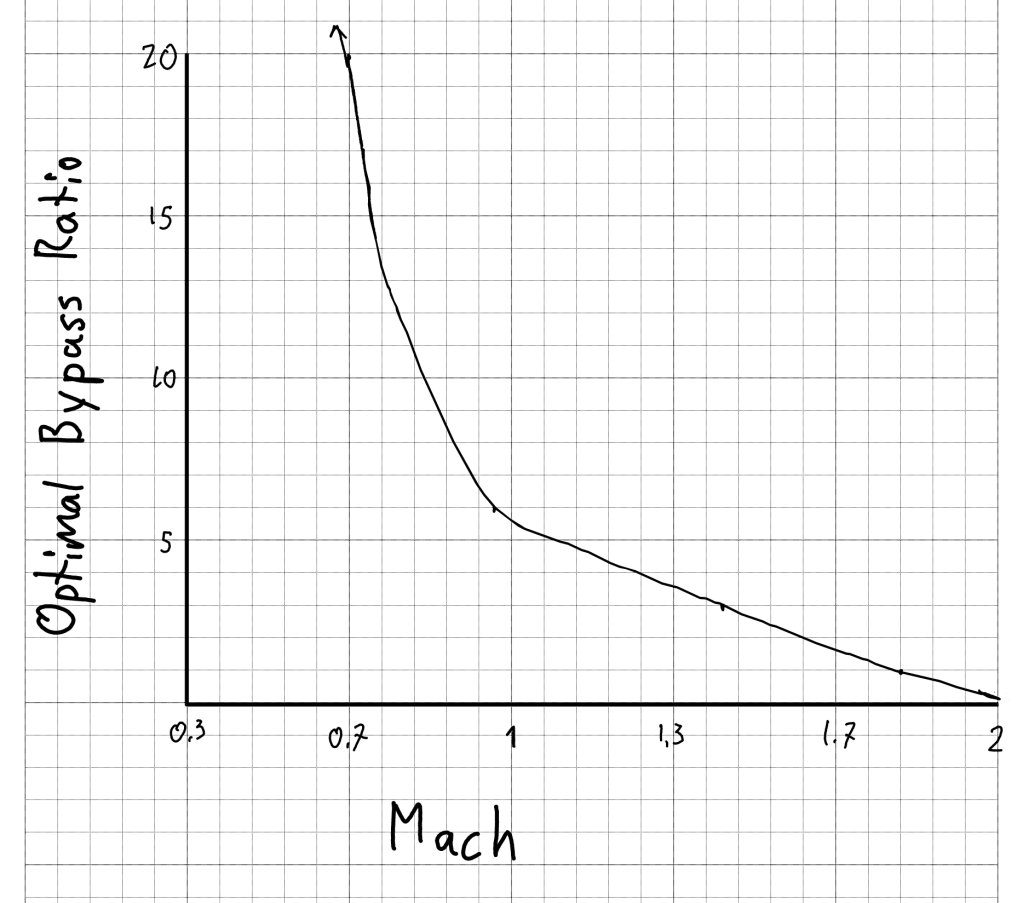

Jet engines are the most efficient when the exhaust is going out the back not too much faster than the plane is flying forwards. At the same time, the inlet in the front isn’t perfect, so you loose a little energy when you slow the air down to Mach 0.5 to go into the engine, and the bigger the engine the more drag that adds. When you add those effects together, for a transonic or supersonic plane, there’s an ideal bypass ratio for each Mach number that doesn’t depend on engines getting more powerful.

If you go too far from the ideal bypass ratio, you get a lot less efficient. The lower bypass ratios that you want for higher speeds are also louder. For a subsonic airliner that’s easy because more efficient and quitter go hand in hand. For a supersonic airliner on the other hand, this presents a challenge because the turbojet that’s ideal for the concord’s Mach 2 cruise can’t meet modern noise regulations. The minimum bypass ratio to meet modern noise regulations is around 4:1, which practically gets you to Mach 1.4 without loosing too much efficiency, and that bypass ratio is also pretty good at Mach 0.95 when you can’t go supersonic.

The other part of getting that maximum efficiency is having an inlet that turns as much of the air’s kinetic energy into pressure as possible instead of heat. Once you go supersonic, you need carefully designed shockwaves to do that, and as you go faster you need more shockwaves to maintain peak efficiency. Two shock inlets are efficient up to about Mach 1.4 and can be pretty simple like the ones on the F-35. Once you have more than that, you have to deal with shockwaves interacting with each other, and generally need moving parts to keep it all organized as you accelerate, or to accept a lot of extra drag.

Material Temperature Limits

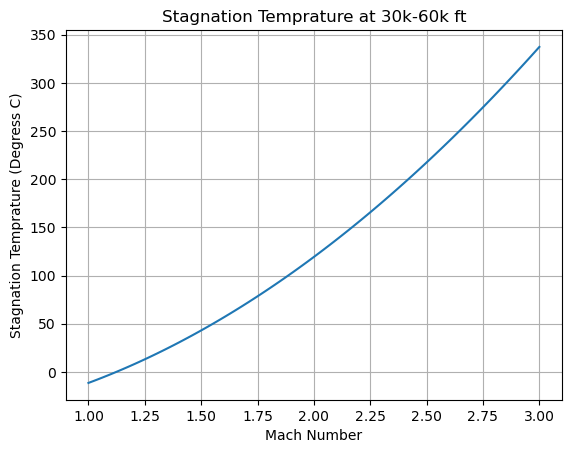

As air hits the nose and the leading edges of the wings, it slows down and heats up. An easy reference to calculate is the stagnation temperature, which is how hot the nose gets, with the wing leading edges getting almost as hot.

Carbon fiber composites are extremely strong and light and can make more complex and efficient wing shapes much more easily. That means you can’t build a competitive modern airliner without composites, and especially a supersonic one that needs a more complex wing. Carbon fiber composites (and the lightest aluminum alloys) are generally limited to around 80C for long term use without degrading. That limits a carbon fiber plane to around Mach 1.6 even with a more temperature resistant nose once you add some safety margin

Addressing “Low Boom” Aircraft

In any discussion of a supersonic airliner, I think it’s also important to address the idea of low boom aircraft. There are generally two versions that have been researched.

The first version is to make a plane with a quieter sonic boom. The idea is basically that, if you can prevent all the little shockwaves from combining into one big one, you get a rumble instead of a boom. The two issues are, at least until you get close to Mach 2, that sort of low boom design adds significant drag, and it’s a percentage reduction, so a giant airliner is still going to sound like a freight train going by.

The other version of low boom is that air get’s colder as you go up, so if you go between Mach 1 and Mach 1.1, you make a sonic boom, but the temperature gradient bends the sound back up so it never reaches the ground. This sounds like a great way to go a little faster over land, but that’s in the Mach 0.98-1.2 ish range where drag is really high, so you get horrible fuel efficiency and need much more powerful engines.

What A Viable Supersonic Airliner Might Look Like

The Boeing Sonic Cruiser

Boeing Sonic Cruiser Schematic – Credit Wikipedia

The Boing sonic cruiser was a technology development program that was the technical predecessor to the 787 program. It was designed for long haul point to point flights at just over Mach 0.95, giving it a 15% speed advantage over conventional airliners.

It’s large double delta wings let it fly efficiently right up to the speed of sound while still being able to use conventional flaps for takeoff and landing. It’s high cruise speed and impressive climb rate could cut an hour off a 6-8 hour flight. While it was meant to cost no more to operate than existing airliners when it was designed, the same advanced technologies could could be applied to a more conventional Mach 0.85 airliner for a 20% fuel savings. The airlines decided that the speed advantage wasn’t worth the extra fuel costs, so Boeing leveraged the program into the 787 instead.

Taking It Supersonic

If we only want to go Mach 1.4, the sonic cruiser offers a great starting point. It’s already designed to fly close to the speed of sound and it’s ~45 degree wing sweep is enough for Mach 1.4. A sharp nose, diverter-less supersonic inlets for the engines like the F-35 has, slightly lower bypass engines, and some minor modifications to the wings would let it cruise at Mach 1.4 over water. It would also retain the same efficiency at both Mach 0.95 and Mach 1.4, and could probably accelerate though the sound barrier in a shallow dive without afterburners.

What You Get

That would get you an airliner with the size and range of a B787 or A350 that only costs about 20% more to operate, and can maintain it’s efficiency on routes that require covering a meaningful distance subsonic. It might only cut about 30% off long haul flight times, but it would be an efficient widebody that could cover 8000 miles with any combination of super and subsonic legs.

That opens up not only the east-west Pacific and north-south Atlantic routes, but also a lot of the over the north pole routes that can’t fly supersonic for the whole flight. Cutting 4 hours off 14 or 16 hour flights for merely the cost of a business class heavy configuration or a 20% ticket premium to cover the extra cost is a business case that might even support a sustainable fleet from more than one manufacturer.

Leave a comment