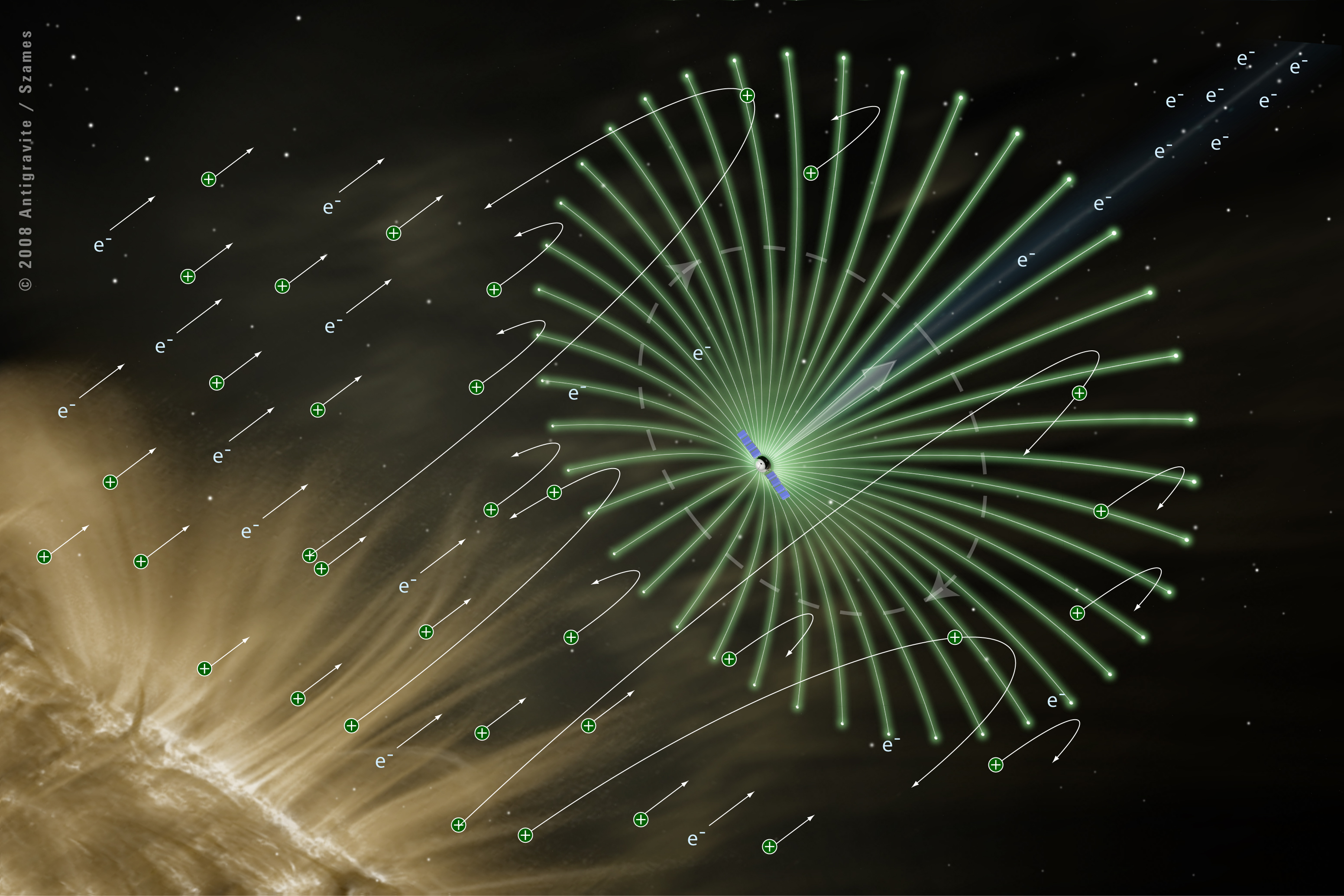

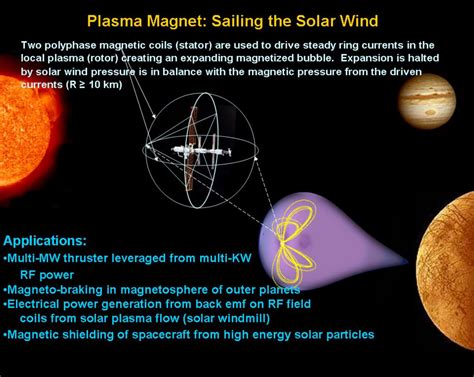

Image Credit – Slough Plasma Magnet NIAC Presentation

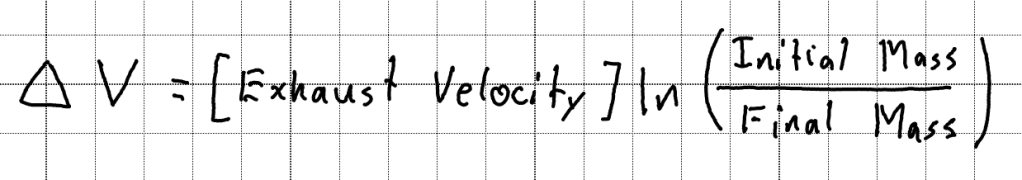

The Tyranny of the Rocket Equation

Why Missions Beyond Earth are Hard

In space, the key metric for how far you can go isn’t distance, because most of the time you’re just coasting, but how much you can change your orbit to get where you want. That’s measured as how much you can change your velocity or delta-v, which can be calculated using the Tsiolkovsky Rocket Equation.

This is the classic form that tells you how much delta-v you have, but for designing a mission, it makes more sense to rearrange it so you input a delta-v and your engine’s performance, and it tells you how much of your ship needs to be propellant.

The payload on a modern two-stage rocket like the Falcon 9 going to low Earth orbit is only about 4% of its launch mass, and has about 10km/s of delta-v to get there, including the 8km/s orbital velocity and gravity and drag losses.

A trip from low Earth orbit to the lunar surface or Mars orbit takes an extra 6km/s from there, requiring another rocket stage that, with regular chemical rockets, cuts your final payload to about an eighth of what you got to low Earth orbit. Round-trip missions, ones to farther destinations, and trying to get the mission done faster all make the tyranny of the rocket equation even worse.

The Limits of Electric Propulsion

The current answer to a lot of high delta-v missions is electric propulsion. It’s incredibly efficient, with solar electric spacecraft often getting 10+km/s of delta-v in a single stage, but suffers from very low thrust.

This makes electric propulsion amazing for things like station keeping that don’t need much thrust and benefit hugely from the efficiency. They also work well for missions to visit things like asteroids or as a kick stage once you’re in solar orbit for similar reasons.

Where electric propulsion struggles is moving in and out of gravity wells. Because the thrust is so low, the orbital mechanics works out a little different. While a chemical rocket only needs 3.1 km/s of delta-v all at once at perigee to escape Earth from low Earth orbit, an electric thruster needs 8 km/s of delta-v to slowly spiral outwards.

Going from low Earth orbit to low Mars orbit takes ~6km/s with a chemical rocket, but ~ 14 km/s with electric propulsion. Once you account for the much lower achievable fuel mass fraction of electric propulsion, it loses most of its efficiency advantage, even just for an Earth-to-Mars transfer. There are a lot of things electric propulsion is good for, but visiting other planets isn’t one of them.

The Limits of Nuclear Thermal Propulsion

Another often proposed solution for making missions beyond Earth easier is nuclear thermal propulsion. The well-understood and relatively safe solid core nuclear thermal rockets can get twice the efficiency of the best chemical rockets while still having plenty of thrust. That makes them really attractive for missions beyond LEO.

The biggest limitation of nuclear thermal rockets is that they don’t scale down very well. The reactor itself can only be made so small, even with weapons-grade uranium, and these engines only get their impressive efficiency when running on hydrogen, which has to be kept at 20K to stay liquid. Storing hydrogen for a long time without it slowly boiling away is doable, but also doesn’t scale down to smaller ships very well.

At least to my thinking, this limits nuclear thermal propulsion to manned missions and related endeavors that require both high delta-v and very large payloads. It’s less of an answer for smaller robotic science or pathfinder missions, and mining bulk material in space is a long way off.

What Is an Inflatable Magnetic Sail

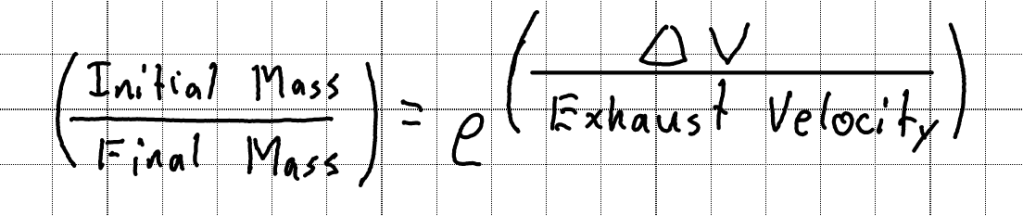

“Sails” in Spaceflight

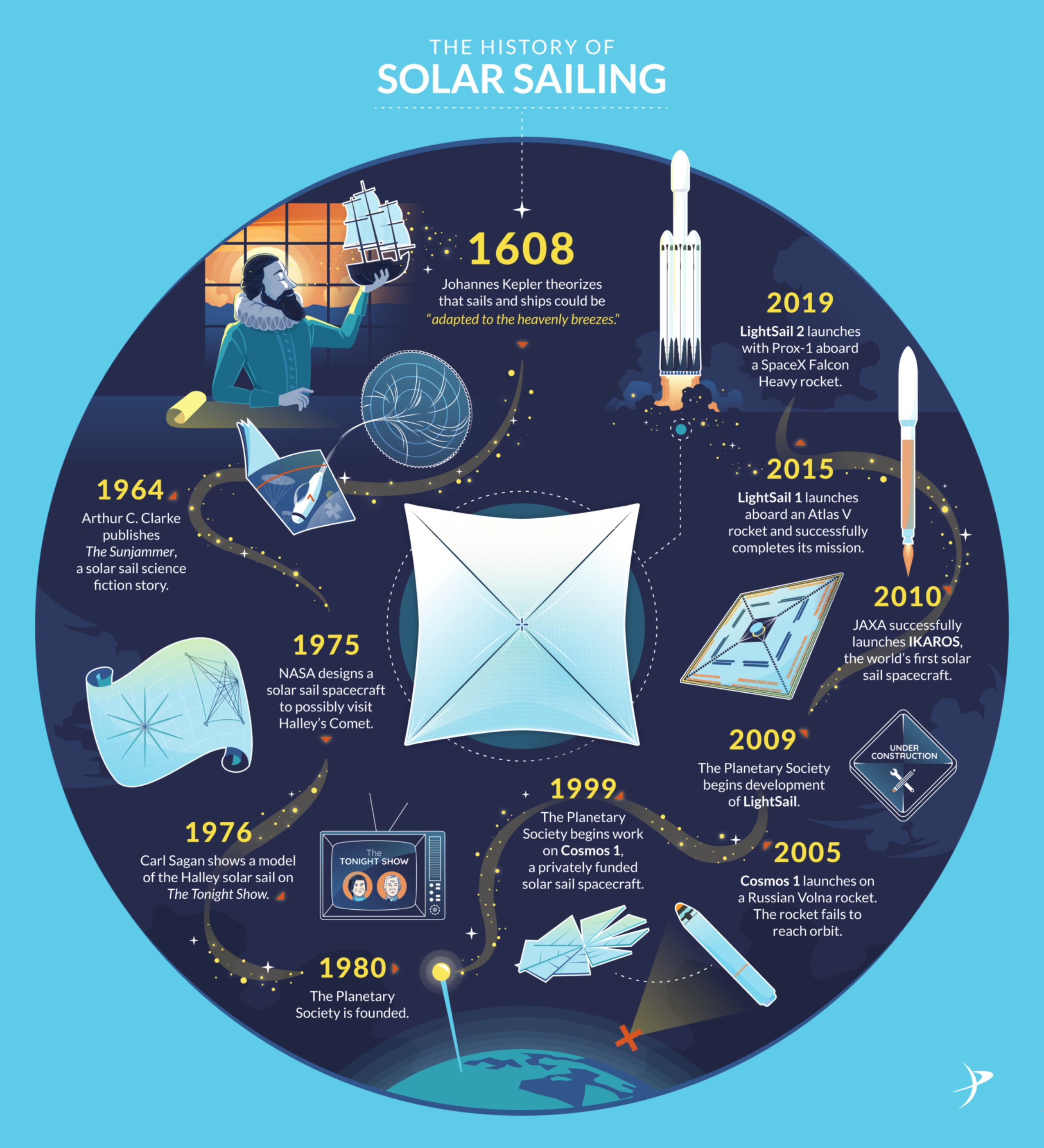

In spaceflight, a sail generally means a propulsion system that, in contrast to a rocket, is pushed on by something outside the spacecraft. The idea originally came from the idea of sailing on the light or plasma wind from the sun, though the sails can also be pushed by artificial beams. The three types are light sails, electric sails, and magnetic sails.

Light sails are the most well-known and look the most like conventional wind sails. They work by having a giant sheet that reflects photons, being pushed by the momentum of light itself. Light sails are theoretically simple and, in principle, the most maneuverable sail technology, but making them light and thin enough to be really useful is extremely challenging.

The second option is an electric sail, which uses long wires spread out from a spinning spacecraft to deflect protons and ions. Using an electron gun to get rid of electrons and positively charge the wires lets them deflect any protons that get close. For complicated physics reasons, they work better farther from the sun than light sails, but the long, thin tethers are much easier to break with a stray micrometeorite.

Image Credit – mdpi.com

The conventional magnetic sail is a giant loop of superconducting wire that, like an electric sail, deflects the solar wind, this time using the Lorentz force instead of charge. The wire loop can theoretically be made much more durable than the electric sail’s tethers, if much more expensive, and without the improved performance far from the sun.

Interestingly, the basic versions of all three solar sail technologies seem to have about the same thrust-to-weight ratio at Earth’s orbital distance.

Inflating a Magnetic Field

The idea of an inflatable magnetic sail takes inspiration from planetary and solar magnetospheres in astrophysics. Earth’s magnetic field, for example, isn’t very strong. Even a big hunk of unmagnetized iron nearby can make a compass read wrong. Despite the field’s weakness, Earth’s magnetic field is still extremely large because it doesn’t fall off with the inverse square law. The plasma around Earth, principally in the Van Allen belts, inflates Earth’s magnetic field to its large size.

Inflatable Magnetic Sail Technology

The idea of an inflatable magnet sail is, instead of using a giant physical magnet to catch the solar wind, you take inspiration from Earth’s magnetic field to make a very large sail with a relatively small physical magnet.

A few different versions have been simulated and lab tested (TRL4) over the last 30 years, so we know they work. Magnetoplasma physics is complicated enough that we don’t know exactly how well without testing it in space. The conservative estimate is about 2 orders of magnitude higher thrust-to-weight ratio than the other solar sail technologies. The real performance might even be slightly better, and fall off a little less as it gets farther from the sun.

Since the physical magnets are small and you can vary the effective size of the sail, it isn’t limited to only being used in the solar wind. It can also be used for powerful and precise breaking against planetary ionospheres, and can push off planetary magnetic fields under the right conditions. This allows for massive practical delta-v savings on orbit insertion and apoapsis lowering maneuvers.

Where Inflatable Magnetic Sails Take You

Round Trip to Mars

One of the current major goals in space exploration is to do a round trip to Mars, first to bring samples back, and eventually for a manned mission. An efficient 9-month transfer each way, spending 2 years on Mars, takes 12 km/s of delta-v. With a trajectory optimized to use a magnetic sail and practical aerobreaking, the delta-V requirement is cut in half. That’s just as good as using a nuclear thermal engine with zero boiloff hydrogen for 3 years or manufacturing fuel on Mars, and can be used synergistically with those technologies on larger missions.

Ice Giant Orbiters

The Ice giants, Uranus and Neptune, have gone relatively unexplored because reaching them in even 10 years with chemical propulsion is incredibly difficult. Even Saturn has only ever gotten a single orbiter mission.

An inflatable magnetic sail provides practical acceleration in the solar wind, allowing it to reach the outer solar system quickly without a massive rocket. The ability to slow down quickly and controlably at the gas giants lets them enter orbit, even from a very fast transfer, again without a massive rocket.

Reaching the Edges of the Solar System

The high acceleration of an inflatable magnetic sail allows even a large probe to easily outrun even New Horizons with a relatively small launch vehicle. That gets it to the farthest reaches of the solar system, to Pluto and even far beyond the heliopause. A sundiving inflatable mag sail even represents a possible path to reach the solar gravitational lens on human timescales.

Leave a comment